We have successfully shipped the Metal rendering backend to millions of users, and I want to write a bit about that. There are varying opinions on Metal in the industry – some claim Metal would not have been needed if only Apple dedicated more attention to OpenGL and Vulkan, some say it’s the easiest graphics API that ever existed. Why even bother with Metal, some ask, if you can just write OpenGL or Vulkan code, and use MoltenGL or MoltenVK to the same effect? Here are my thoughts on the API.

Why Metal?

When Apple announced Metal at WWDC in 2014, my initial reaction was to ignore it. It was only available on the newest hardware, which most of our users didn’t have. And although Apple claimed that Metal solved CPU performance issues, for us to optimize for the smallest market would mean the gap between the fastest devices and the slowest devices grows even more. At the time, we were running OpenGL ES 2 only on Apple, and also starting to port to Android.

Fast forward two and a half years, and here’s how the Metal market share looks for our users:

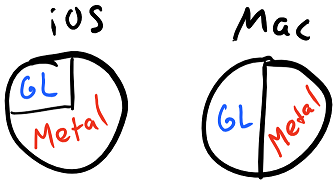

This is much more appealing than it used to be. It is still the case that implementing Metal does not help the oldest devices, but the GL market on iOS keeps shrinking. Plus, the content that we run on oldest devices is frequently different from the content that runs on the newest devices, so it definitely makes sense to dedicate some effort to make these devices faster. Given that your iOS Metal code will run on Mac with very few changes, it could make sense to use it on Mac as well even if you are mobile-focused (we currently only ship Metal builds on iOS).

I think it is worthwhile to analyze the market share in a bit more detail. On iOS, we support Metal for iOS 8.3+. While there are some users who can’t run Metal because of OS version restrictions, most of the 25% who still run GL are simply using older devices that have SGX hardware. They also don’t have any OpenGL ES 3 features, and we’re content with running a lower-end rendering path there (although, we’d love all devices to go Metal. Fortunately, the GL/Metal split will only improve). On Mac, Metal API is newer and the OS plays a pretty significant part. You have to use OSX 10.11+ to use Metal, and half of our users simply have a more dated OS. It’s less about the hardware and more about the software (95% of our Mac users run OpenGL 3.2+).

So, given the market share, there are still other options that do not involve porting to Metal. One of them is to just use MoltenGL, which would use the OpenGL code we already have, but supposedly be faster; another to port to Vulkan (to get better performance on PC, and eventually Android); or use MoltenVK. I have briefly evaluated MoltenGL and was not too thrilled with the results. It took some effort to make our code run at all, and while performance was a bit better compared to stock OpenGL, I was hoping for more. As for MoltenVK, I think it is misguided to try to implement one low-level API as a layer above another one. You’re bound to get impedance mismatch that will result in suboptimal performance. Maybe it will be better than the high-level API you used to use, but it’s unlikely to be as fast as possible, which supposedly is why you’re choosing a low-level API to begin with! One other important aspect is Metal implementation is much simpler than a Vulkan one – more on that later – so in some sense I’d prefer a Metal -> Vulkan wrapper instead of a Vulkan -> Metal.

It is also worth noting that there is no GL driver on iOS 10 on the newest iPhones, apparently. GL is implemented on top of Metal, which means using OpenGL is only really saving you a bit of development effort – not that much, considering that the promise of “write once, run anywhere” that OpenGL has does not really work out on mobile.

Porting

I would say that porting to Metal was a breeze overall. We have a lot of experience working with different graphics APIs, ranging from high level APIs like Direct3D 9/11 to low level APIs on console platforms. This gives a unique advantage of being able to comfortably use an API like Metal that is simultaneously reasonably high level but also leaves some tasks like CPU-GPU synchronization for the app developer to do.

The only hurdle was getting our shaders to compile. Once that was done and it was time to write the code, it became apparent that the API is so simple and self-explanatory that the code practically wrote itself. I got the port that rendered most things in a suboptimal fashion running in about 10 hours in a single day, and spent two more weeks cleaning up the code, fixing validation issues, profiling and optimizing, and doing general polish. To get an API implementation in this time frame speaks volumes of the quality of the API and the toolset. I believe there are several aspects that contribute:

- You can develop the code incrementally, with good feedback at every stage. Our code started by ignoring all CPU-GPU synchronization, being really suboptimal about certain parts of state setup, using built-in reference tracking for resources, and never running CPU and GPU in parallel to avoid running into issues. The optimization/polish phase then converted this into something we could ship, never losing the ability to render in the process.

- The tools are there for you; they work and they work well. This is not as much of a surprise for people who are used to Direct3D 11, but this is the first time on mobile where I had a CPU profiler, a GPU profiler, a GPU debugger, and a GPU API validation layer that all worked well in tandem, catching most issues during development and helping optimize the code.

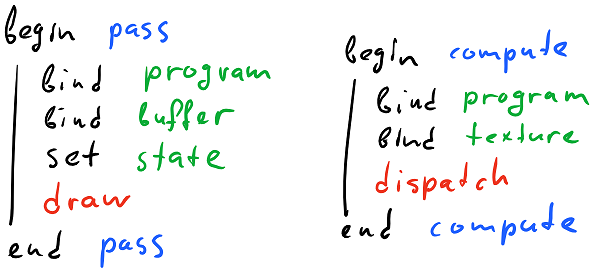

- While the API is somewhat lower level than Direct3D 11, and it leaves some key low-level decisions to the developer (such as the render pass configuration or the synchronization), it still uses a traditional resource model where each resource has certain “usage flags” it has been created with but does not require pipeline barriers or layout transitions, and a traditional binding model where each shader stage has several slots you can freely assign resources to. Both of these are familiar, easy to understand, and require very limited amount of code to get going fast.

One other thing that helped is that our API interface was ready for Metal-like APIs. It is very lean but it exposes enough detail (such as render passes) to be able to easily write a performant implementation. At no point in our implementation did I need to save/restore state (many API interfaces suffer from this, particularly due to treating render target setup as state changes and resources/state binding persisting through that) or make complicated decisions about resource lifetime/synchronization. About the only “complicated” piece of code needed to render is one that creates the render pipeline state by hashing bits that are needed to create one – pipeline state objects are not part of our API abstraction. Even that is pretty straightforward and fast. I will write more about our API interface in a separate post.

So, a week to get the shaders compiling, two weeks to get a polished optimized implementation((Yeah, okay, and maybe a week to fix a few bugs discovered during testing)) – what are the results? The results are great. Metal absolutely delivers on the performance promise. For one, the single threaded dispatch performance is noticeably better than with OpenGL (shrinking the draw dispatch part of our render frame by 2-3x depending on the workload), and this is given that our OpenGL implementation is pretty well tuned in terms of reducing redundant state setup and playing nice with the driver by using fast paths. But it does not stop there – multithreading in Metal is trivial to utilize provided that your rendering code is ready for it. We haven’t switched to threaded draw dispatch yet but are already converting some other parts that prepare resources to happen off the render thread, which, unlike with OpenGL, is pretty much effortless.

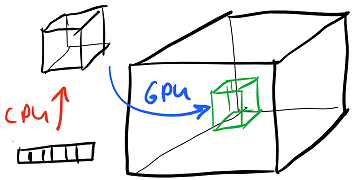

Beyond that, Metal allows us to fix some other performance issues by giving easily accessible and reliable tools. One of the central parts of our rendering code is the system that computes lighting data on the CPU in world space and uploads it to regions of a 3D texture (which we have to emulate on OpenGL ES 2 hardware). The updates are partial so we can’t duplicate the entire texture and have to rely on however the driver implements glTexSubImage3D. At one point we tried to use PBO to improve update performance but faced significant stability issues across the board, both on Android and iOS. On Metal, there are two built-in ways to upload a region – MTLTexture.replaceRegion that you can use if GPU is not currently reading the texture, or MTLBlitCommandEncoder (copyFromBufferToTexture or copyFromTextureToTexture) that can upload the region asynchronously just in time for GPU to start using the texture.

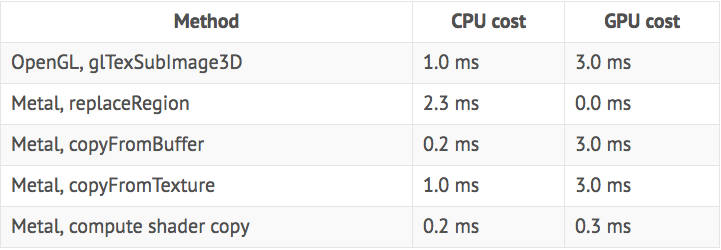

Both of these methods were slower than I’d like. The first one wasn’t really available since we had to support efficient partial updates, and it worked purely on CPU using what looked like a very slow address translation implementation. The second one worked but seemed to use a series of 2D blits to fill the 3D texture which were both pretty expensive to set up commands for on the CPU side and also had a very high GPU overhead for whatever reason. If this were OpenGL it would be over – in fact, the performance of these two methods roughly matched the observed cost of a similar update in OpenGL. Fortunately, this being Metal, it has easy access to compute shaders – and a super simple compute shader gave us the capability to do a buffer -> 3D texture upload that was very fast on CPU and GPU and basically solved our performance problems in this part of the code for good((The numbers are for 128 KB worth of data updated per frame (two 32x16x32 RGBA8 regions) on A10)):

As a final general comment, maintaining Metal code is pretty much effortless as well. All extra features we had to add so far were easier to add there than on any other API we support, and I expect this trend to continue. There was a bit of a concern that adding one more API would require constant maintenance, but compared to OpenGL this does not really require much work. In fact, since we won’t have to support OpenGL ES 3 on iOS any more, this means we can simplify some OpenGL code we have as well.

Stability

Today on iOS, Metal feels very stable. I am not sure what the situation was like at launch in 2014, or what it is like on Mac today, but both the drivers and the tools for iOS feel pretty solid.

We had one driver issue on iOS 10 that had to do with loading shaders compiled with Xcode 7 (which we fixed by switching to Xcode 8), and one driver crash on iOS 9 that turned out to be a result of misusing nextDrawable API. Other than that we haven’t seen any behavioral bugs or any crashes. For a relatively new API, Metal has been very solid across the board.

Additionally, the tools you get with Metal are varied and rich; specifically, you can use:

- A pretty comprehensive validation layer that will identify common issues in using the API. It’s basically like Direct3D debug – which is familiar for Direct3D but pretty much unheard of in OpenGL land (in theory, ARB_debug_callback is supposed to solve this; in practice, however, it’s mostly unavailable and when it is, not terribly helpful)

- A working GPU debugger which shows all commands you have dispatched along with their state, the render target contents, the texture contents, etc. I don’t know if it has a functioning shader debugger because I never needed that, and the buffer inspection could be a bit easier, but it mostly does the job.

- A working GPU profiler which shows per-pass performance stats (time, bandwidth) and also per-shader execution time. Since the GPU is a tiler you can’t really expect per-drawcall timings, of course. Having this level of visibility – especially considering the complete lack of any GPU timing information in graphics APIs on iOS – is great.

- A working CPU/GPU timeline trace (Metal System Trace) that shows the scheduling of CPU and GPU rendering workload (similar to GPUView but actually easy to use), modulo some UI idiosyncrasies.

- An offline shader compiler that validates your shader syntax, occasionally gives you useful warnings, and converts your shader into a binary blob that’s pretty fast to load at runtime and is reasonably well optimized beforehand (thus reducing the load times since the driver compiler can be faster).

If you come from Direct3D or console world, you may take every single one of these for granted. Trust me, in OpenGL every single one of these is unusual and is met with excitement, especially on mobile where you are used to dealing with occasionally broken drivers, no validation, no GPU debugger, no GPU profiler that is helpful, no ability to gather GPU scheduling data, and being forced to work with a text-based shader language that each vendor has a slightly different parser for.

Conclusion

Metal is a great API to write code for, and ship applications with. It’s easy to use, it has predictable performance, and it has robust drivers and solid toolset. It beats OpenGL in every single aspect except for portability, but the reality is that you really only should have used OpenGL on three platforms (iOS, Android and Mac). Two of those platforms now support Metal; additionally, the portability promise of OpenGL is largely not fulfilled as the code that you write on one platform very frequently ends up not working on another for different reasons.

If you are using a third-party engine like Unity or UE4, Metal is already supported there; if you aren’t and you enjoy graphics programming or care deeply about performance and take iOS or Mac seriously, I strongly urge you to give Metal a try. You will not be disappointed.